Irwin Hollander: INSIDER OUTSIDER

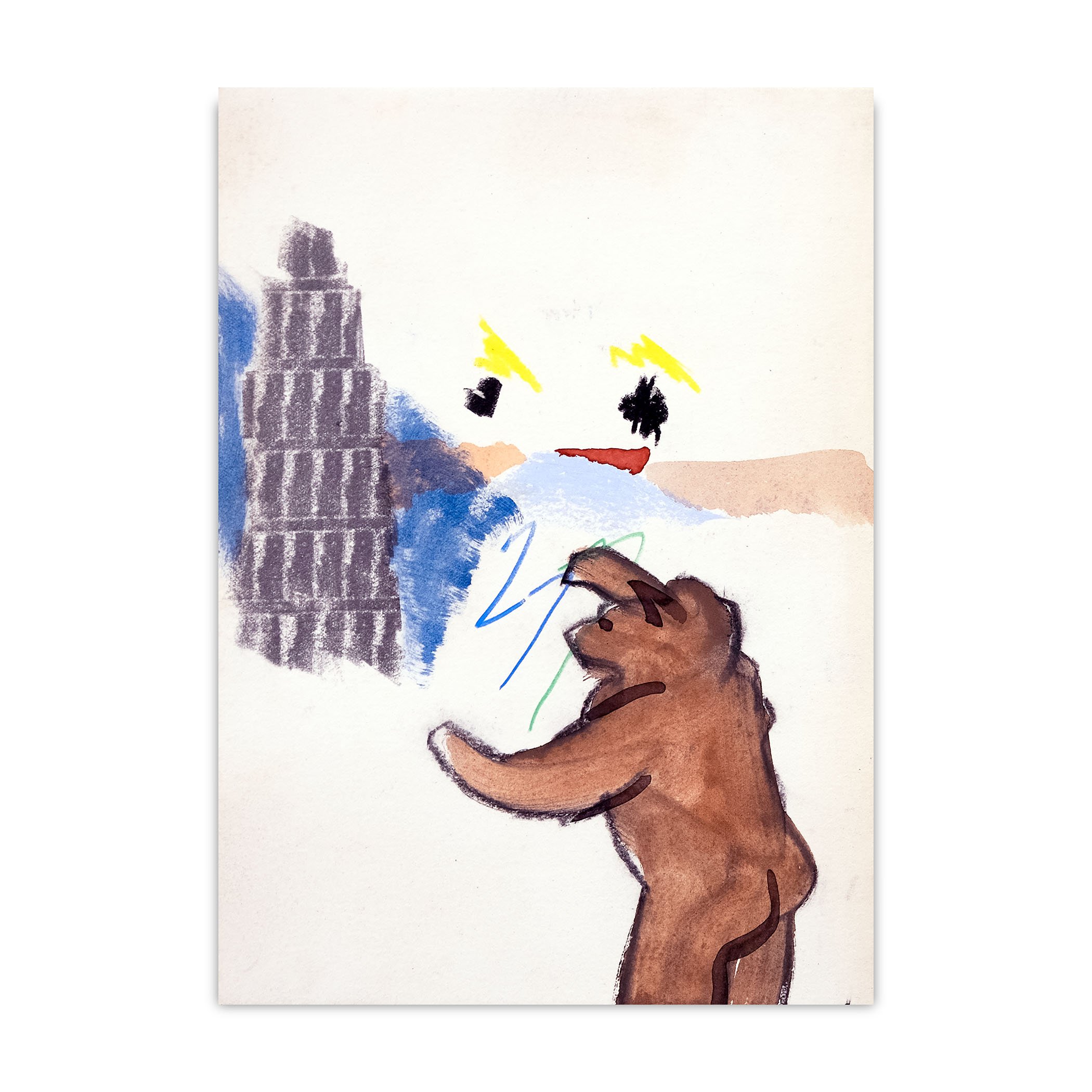

Untitled (Teddy bear and profile), c. 1984 - 2002. Lithographic crayon, mixed media on paper

30 x 22 ¼ inches.

For many people, Irwin Hollander is known for his collaborations with other artists. In his lithography studio, he worked with the likes of Willem de Kooning, Roy Lichtenstein, Sam Francis, Ellsworth Kelly, Louise Nevelson and Robert Motherwell. Hollander became a lithographer in part because he wanted to work closely with artists. In his work as a printmaker he got as close to the artist’s thoughts, feelings and process as possible, in order to produce work that would best relect the artist’s intention. References to this period of his life, working as a vehicle for the work of others, appear throughout his hand- written journals and sketchbooks. Irwin passed away in 2018 and we, presenters of this exhibition of his own artwork, are only connecting to him now, several years and layers later. In this position we feel very much that the tables have turned: it is we who are looking in, studying Hollander-as-artist, trying to imagine his thoughts and motivations as he made his own artwork in Wells Bridge, a life after New York City and his printmaking career.

As we make our forays into Hollander’s world we see that he was both an insider and outsider artist. Though he lived at various times in metropolitan cities—most deined by his time in New York City— his 1984 move 200 miles north to Wells Bridge seems to have cleaved the two halves of his life; one in which he produced the artwork of others (and taught the trade) and the other in which he made his own.

In terms of his position as an insider to the art world, he had art training, and subsequently headed two seminal lithography studios serving the best artists of the time (whose works, printed by Hollander, reside in many major collections). Beginning in 1965 he began teaching lithography at Pratt Institute in New York, and later Cranbrook Art Academy and Wayne State University in Detroit. In his own artwork, he draws from art history and its icons, frequently including ‘art jokes’ with tongue-in- cheek references of the “fine artist”—bears drawing the Leaning Tower of Pisa, for instance.

On the other hand, Hollander’s work most parallels the approach of an outsider artist. While he often used high-quality paper—presumably stock from his master printer days—he was also known to paint and draw on whatever was available, such as the slate tiles from his own roof when it was replaced. As for paint media, his longtime friend Elizabeth Nields laughs that “Whatever he reached for he would try—and wouldn’t necessarily follow the rules.” In addition to gouaches and traditional paints, he used lithography techniques, and borrowed her potter’s glazes; used spray paint, and sealing wax.

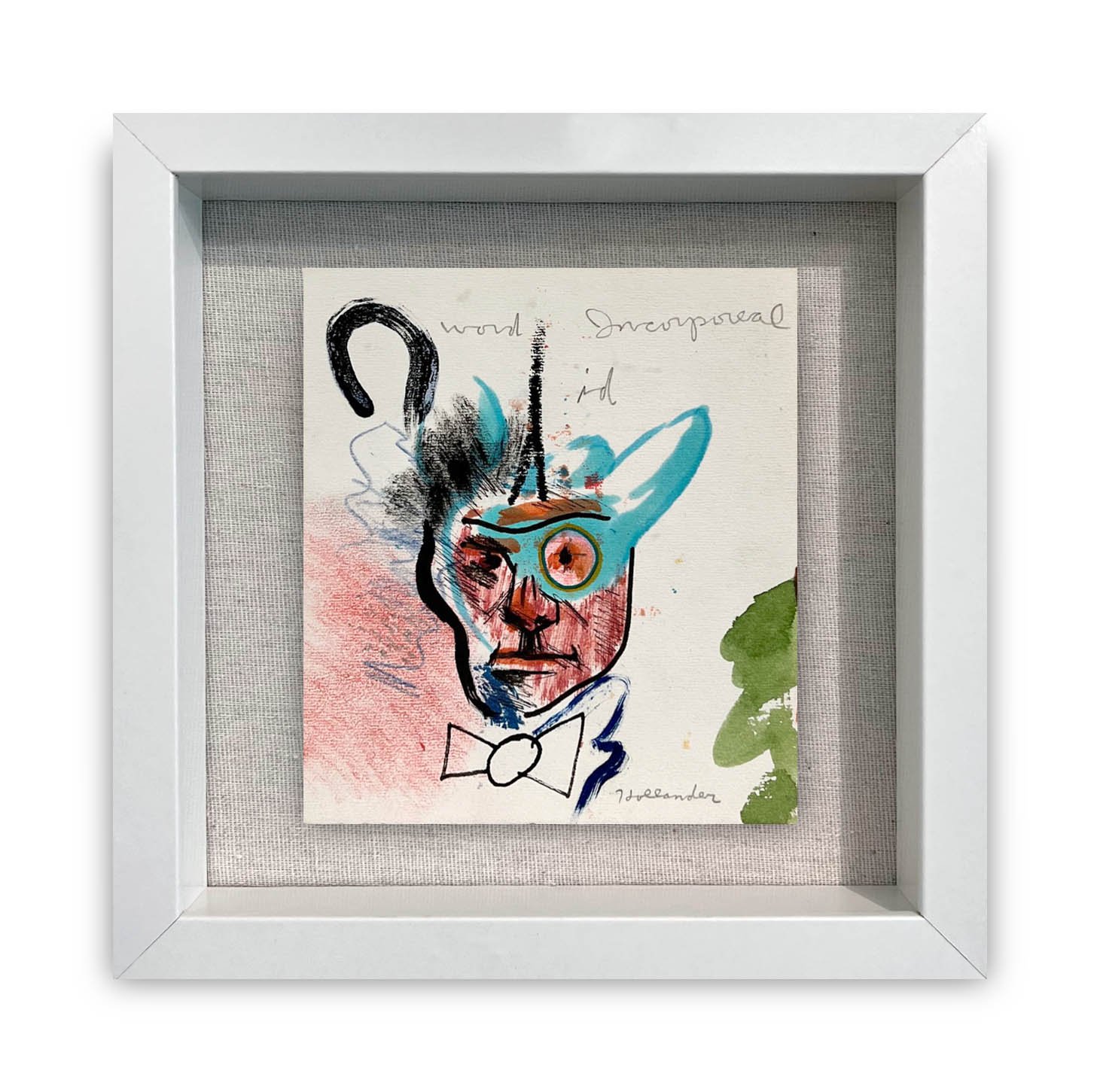

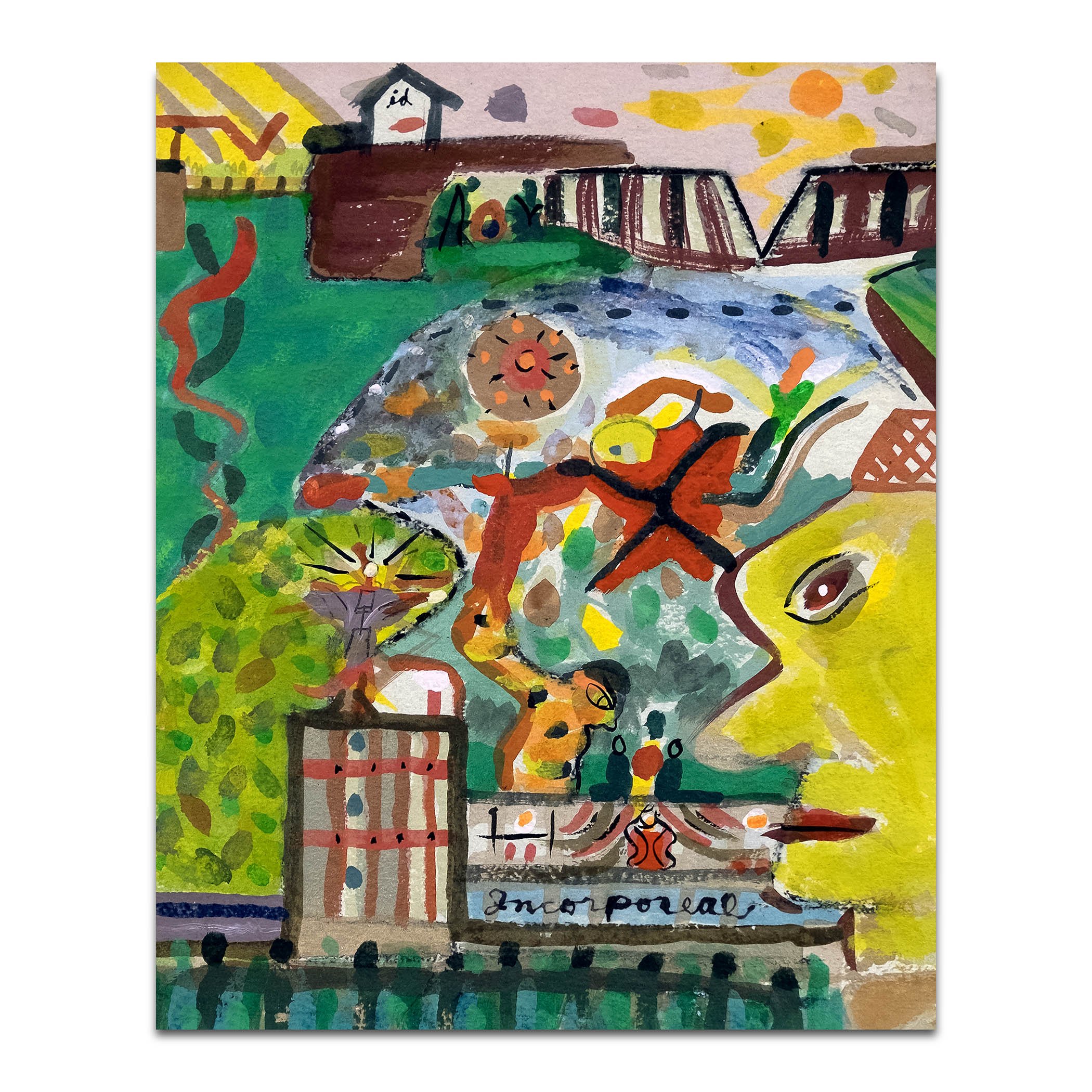

Moreover his work cannot be handily defined as belonging to this or that movement or art-historical period; it seems to exist in its own world. It is highly personal, often diaristic, noting places and names from the past; tropical memories of his time in the Pacific; icons of his Jewish heritage and Brooklyn upbringing. There is a sense, moreover, of travels between his own inner and outer reality: a mix of surreal and almost metaphysical characters and dimensions, together with images of his environment: the bridge, his home, the river, the railroad. The repeated use of the term INCORPOREALITY in his work seems to underscore this feeling of free-loating—from and between place, time, and history.

Hollander’s paintings often depict the joining of two parts: himself and Deanna, his longtime girlfriend and muse (id, the combined initials of their first names, and a clever double-entendre to boot, is the subtle seal of identity given many works); the bear and the doll, and human pairs, in close lock. Insider and outsider, in Hollander’s case, should also not be seen as discrete parts but mutually generative, one always coloring the other.

It is in this space we have hopefully connected with Hollander and his time in Wells Bridge. It is a way in, but the journey will be, as his wild, poetic, funny, and singular paintings suggest, full of curves. As one painting/poem puts it, “The story unfolds like noodles...Kid.”