“Shrub ethos” with Derek Stroup

In this exchange, Derek Stroup discusses his interest in Floyd Bennett Field, the non-monumental thread in his art-making, shrubbery and his current exhibition at KIPNZ, Radiant Fields.

Utopia Library, 2018-present. (Detail) Screen ink on paper, archival pigment print and mylar on plywood.

Kenneth (KIPNZ): I'm really curious, what drew you to plywood?

Derek: At first, I just didn't want to work on a white background. I had this gut feeling that I didn't want a white surround for these works I was making. And so I got some wood that was inexpensive. As I was cutting it up and working with it, it has a really complex pattern to it, like a Moiré pattern in silk or something. It isn't tree rings. It's just that the wood has been peeled apart to make the plywood and you get this wavy, atmospheric, almost Baroque sensation to the background. It adds something different from the geometry of these little markers.

Kenneth: I think there's something interesting in the tension between the utility of materials you're choosing; though inexpensive, they have an ornate feel to them. Perhaps there is a highbrow and lowbrow tension at play?

Derek: Maybe. I like the plywood screwed directly onto the wall. Almost like paneling. I have this fantasy of some sort of Home Depot Versailles; paneling room after room with this plywood with this marker system on it. Something that is this organic, beautiful space, but still has these echoes of Home Depot in it.

Installation view: “Radiant Fields: Artwork by Derek Stoup” KIPNZ, 2024

Natalie (KIPNZ): It has a lot of warmth, too. The fact that this plywood has deepened in color and aged a little bit, which is a nice aspect.

Derek: It tempers over time and gets nicer actually. There’s a slight green undertone when you get it. And then over time it gets warmer. It gets warmer and warmer and more orange and that green undertone vanishes. That's a nice added benefit to time passing.

Kenneth: So what drew you to the universal markers? There are these swatches of color on the plywood that repeat throughout a lot of your works. I'm curious where those came from. And which came first? Did you want to do the markers and you were looking for something to put them on? Or you were drawn to the plywood and then thought about the markers?

Derek: I think the markers did come first. At their simplest they're silkscreened ink onto paper and then just cut up in different sizes and shapes, sort of making choices as I go along. And what they come from I don't exactly know. In speaking with my wife Terra, who's a city planner and urban designer; she pointed out that they're similar to what they call ‘delineators.’ Things like those little reflectors on the side of the road. They're not caution signs. They're not “no parking” signs. They are just those little zips saying something is here. And I've often thought that these are kind of like language - what's the most basic unit of communication? Just saying “I'm here.” It's an alphabet; something saying “I'm here,” just in a different size and color and shape.

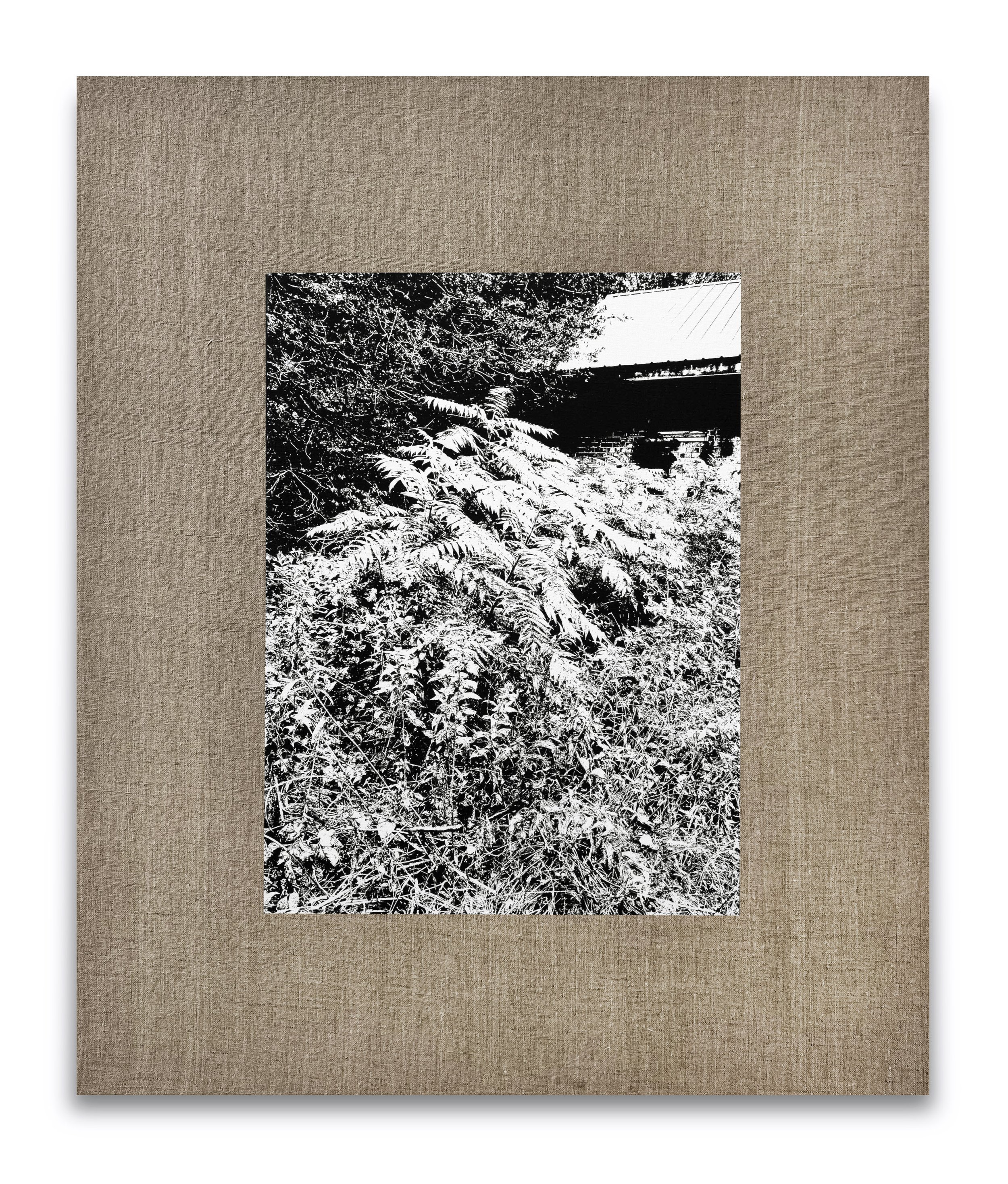

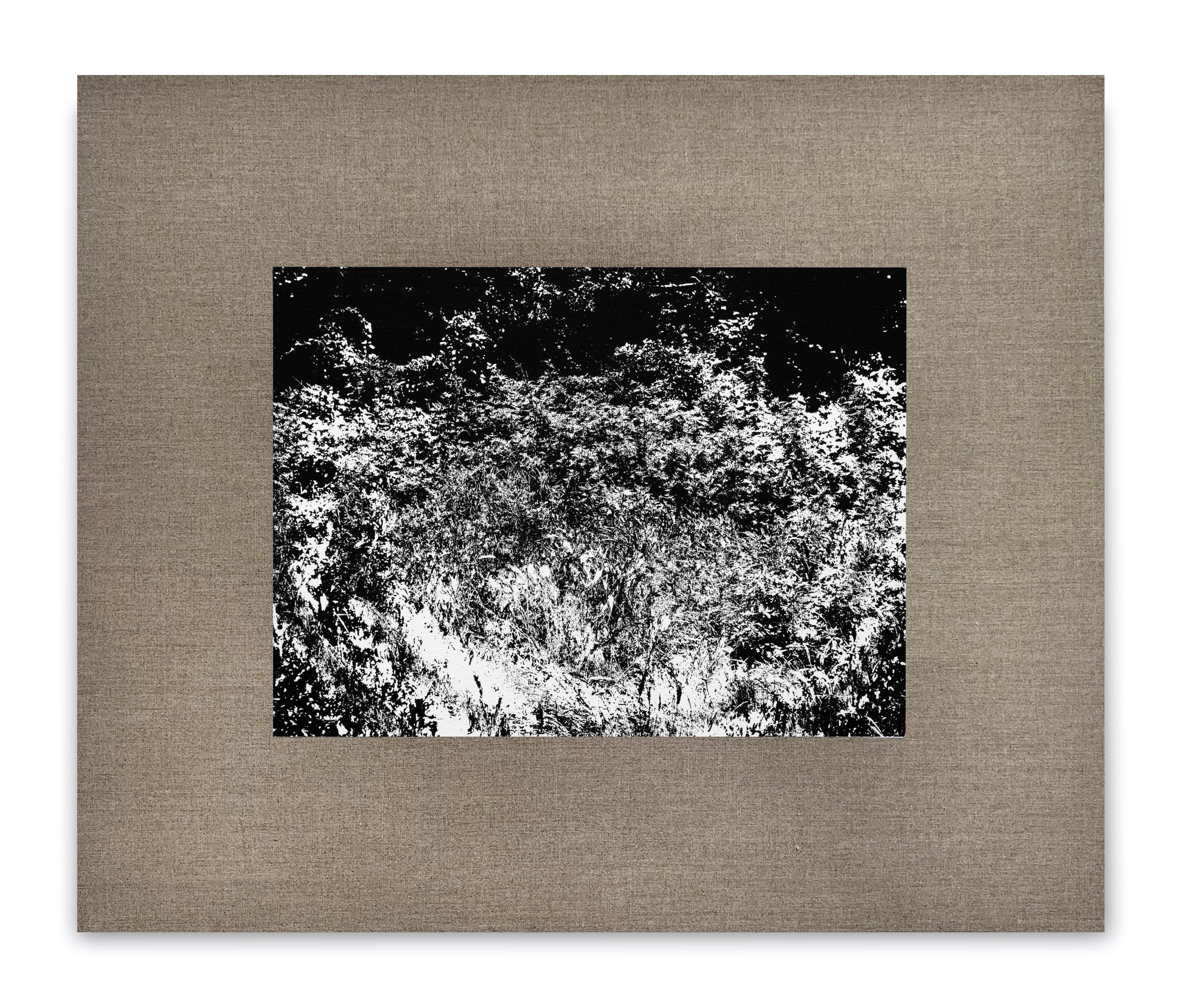

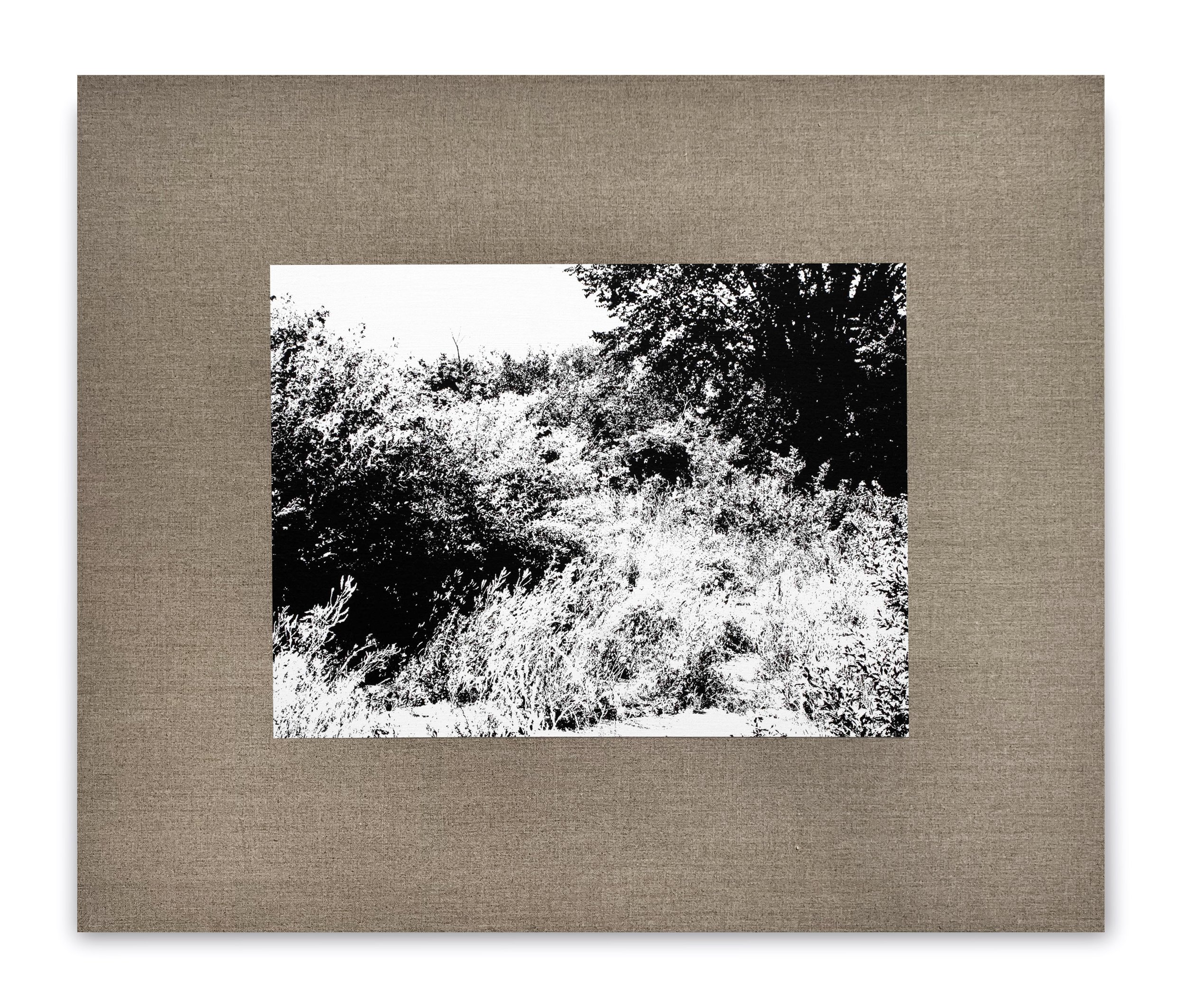

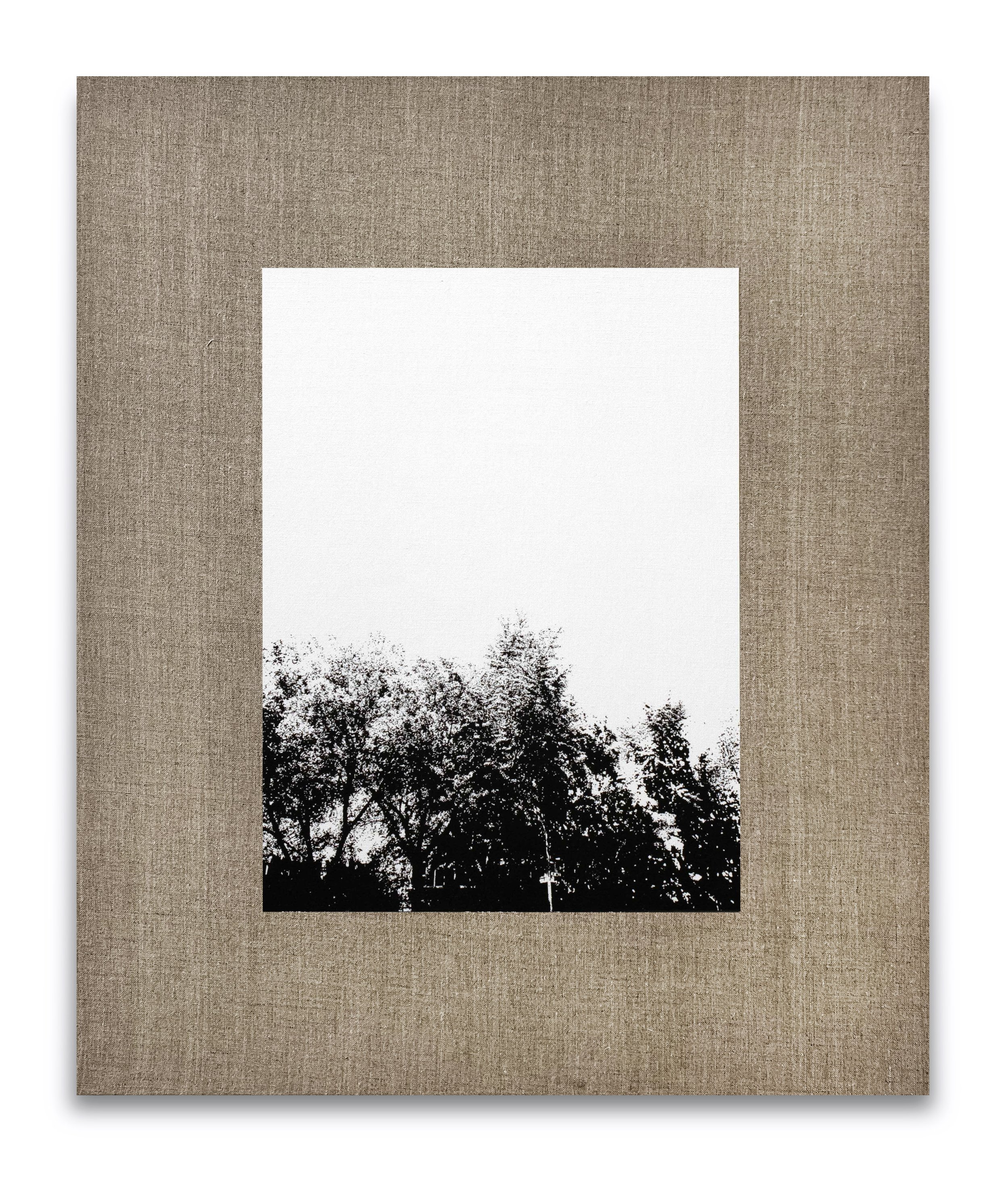

Brooksvale Edge (with marker), 2023. Two parts: Screenprint on linen; screenprint paint on linen. 24 x 37 inches. Unique.

Kenneth: Earlier you mentioned an interesting thought that came from considering the early satellite, Sputnik. Can you explain that again?

Derek: A student of mine did this presentation on design, and his presentation topic was Sputnik. The student was Erik Leuchs. He was a terrific student and he was talking about Sputnik as an existential object. The reason why he felt Sputnik was ultimately like an art object is that all it did was beep at a regular rate. Scientists can do all kinds of stuff with that information but it's such a strange thing. It was just proclaiming its existence to the universe for however long the beeping lasted. And it was broadcasting this one signal over and over - that’s all it did. And art objects are kind of like that. They just proclaim a signal “I'm here,” and then we decide how we feel about it. But to me all art objects are just proclaiming “I'm here,” I'm a resident now of this situation.

Natalie: We were talking a little bit yesterday about how the universal markers are like a signifier of information, merely announcing themselves as information, even if that information is not known. And you also said that in a lot of your work, it's always a question of how much information is going to be visible after all of the processes have finished; after you've washed the emulsion off, after you’ve pushed an image to be only pure black and pure white. Could you say a thing or two about that?

Floyd Bennett Field Western Road (blue), 2023. Screen emulsion on canvas. 52 × 68 inches.

Derek: Every step of the process I lose information. Starting with an iPhone photo or starting with a high resolution digital file - I have to convert that information to a single channel of black and white. So information gets lost. And then you print that really big and information is lost again. And then you print it onto canvas and even more information is lost. So why am I doing that? I mean, we love photography and we think at times how much detail it can bring forward. And I'm sort of seeing maybe the opposite. What can survive this loss process of surrendering control and surrendering information as I navigate through it? Some things can survive that process. And some things don't. I sort of go through this elaborate adventure making the file and making the print and often it doesn't work. But these pieces in the show, there's still enough texture there.

Natalie: I think you've actually reintroduced texture in different ways with the play in the grain, with the linen, with the crisp edge of the screenprinting; it's like a new place. It’s a new object from how it started. I think it's an interesting way of completing the process and reintroducing new types of information that is three dimensional now.

Derek: That’s really nice. Yeah, and scale is really important to me. I was trained as a sculptor. So, scale is the foremost thing in my mind. And photography is weird because scale is the last decision you make. It’s up in the air, it can totally be anything. It can be on your iPhone, a tiny little Instagram photo, it can be four by six feet, it can be ten by twelve feet - and all that happens in the end, which is really kind of interesting. You can procrastinate and kick the scale question down the road. Whereas with a painting, that's the first thing you decide. And you can't really change that readily. I hope that the physicality, the texture of it, even the way that the canvas is kind of flip floppy on the wall, activates in these new ways.

Installation view: “Radiant Fields: Artwork by Derek Stoup” KIPNZ, 2024

Kenneth: And then, to me, in contrast to the large emulsion pieces, the silkscreen works, despite being reduced to just black and white pigment, feel hyper-detailed and full of information.

Derek: Through that process, the contrasts are so important because as you say, there's no gray in these images, only blacks and whites. So you're seeing texture and detail in a different way. If you took the photograph yourself and didn't do anything to it, that information would be there. But the contrast is now so great that they just appear, to our eyes, to be more detailed in a way.

Kenneth: To me, that's something throughout your work, Derek. Trying to trace the idea that no image is neutral; the way the eye plays a role, how scale plays a role, how process plays a role, erasing or magnifying information. We kind of live in this world where we think images are facts but in every method here, some mediation is happening that affects what you see.

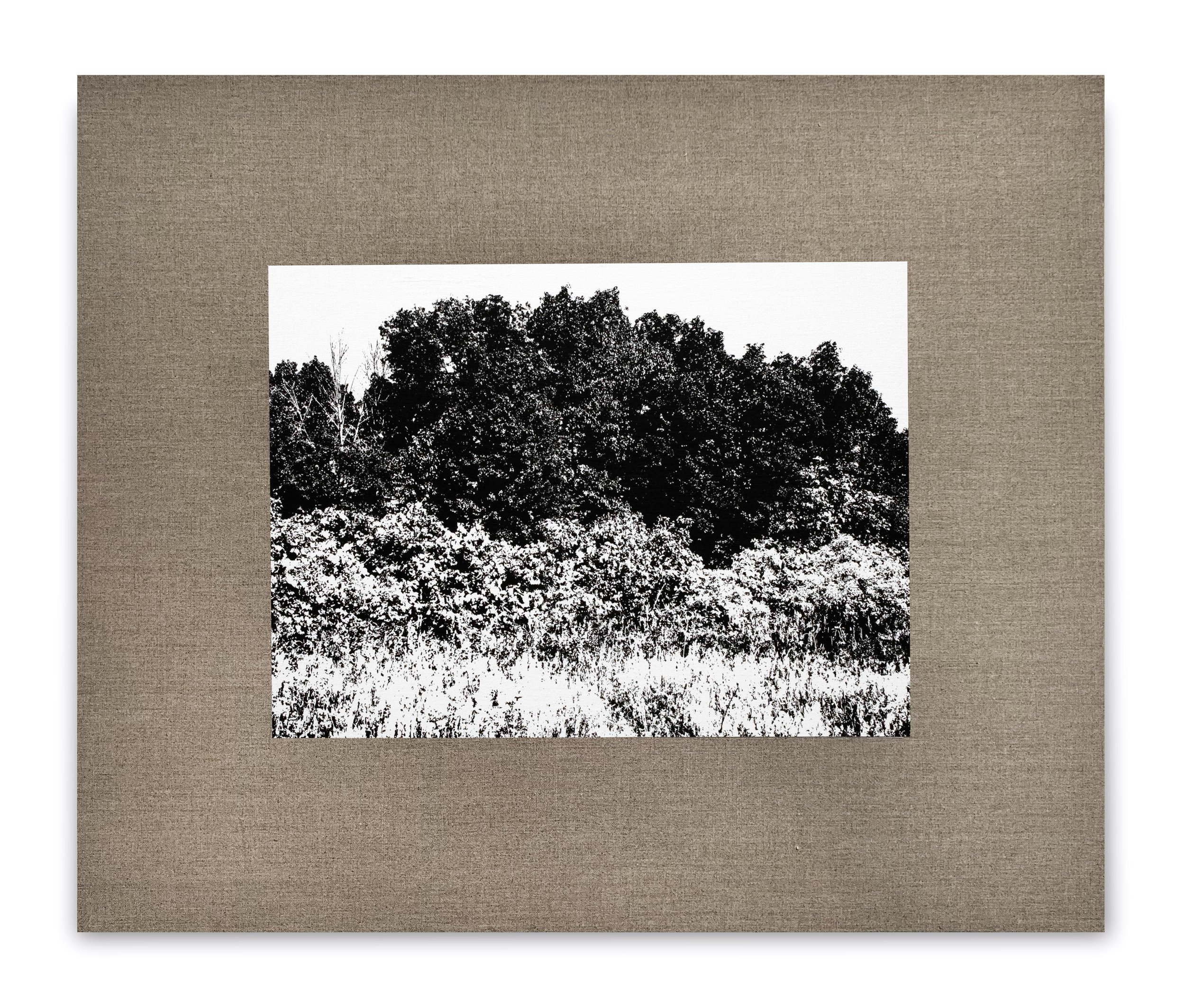

Dandelions, 2023. Screen print on linen. 24 x 29 inches. Unique.

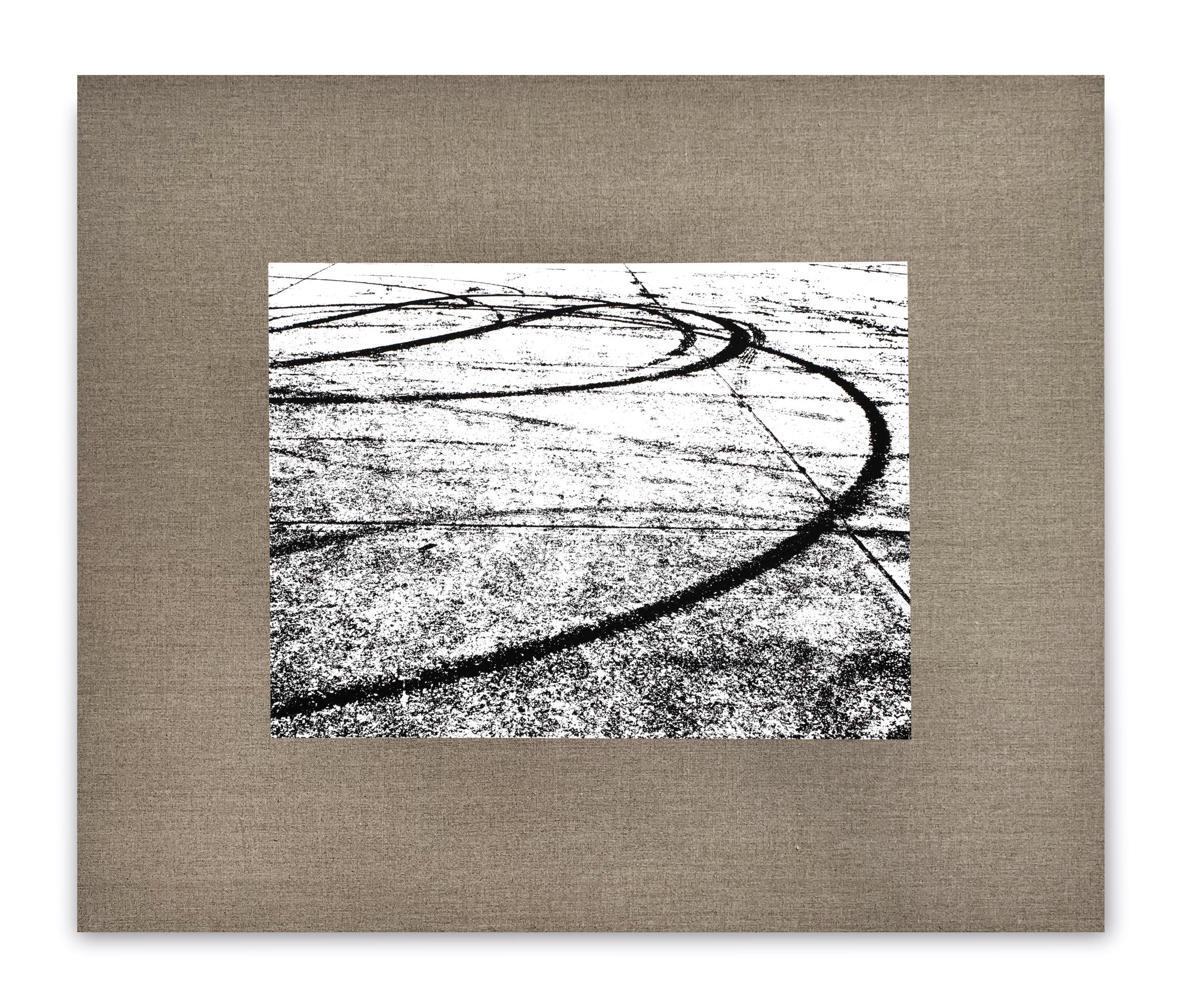

Derek: Yeah, I’ve been thinking about the way your eye creates the grays in those pictures. There's grasses and things like that, and the extreme texture of that grass, created from the contrasts between black and white, is what gives you the sensation of grays. Right after grad school, I worked for Robert Irwin for about a year. And his main preoccupation was with perception and awareness. And I knew I was a different kind of artist then. I sort of knew what he was doing, but I was not interested in it. And then thirty years later, somehow, there's some element of that. A phenomenological curiosity that he had bubbling up in these projects. It's interesting how latent these things can be. For me, those pictures are really truly about a tactile, physical relationship with radiation. And almost all of them are about weeds. Weeds are plants that know exactly what to do with radiation. They know how to relate to the sun without any problems whatsoever. We have radiation problems. It's on everyone's mind these days, what's happening to our planet. But these are images of success and there’s something about physically pulling the screen for me - almost a sunburned quality in some of those pictures. It is really tactile and physical. And working out at this old abandoned airport, Floyd Bennett field which is in Brooklyn. It’s an old empty airport, an abandoned airport. So there’s just huge slabs of concrete. And you're baking when you're out there as a human being in the sun, but the poison ivy seems fine. It's there at the edge of the runway just thriving. They could mow it down and you’d still see little tiny ones just making their way through the cracks of the concrete and a million other points like that. It is a carnival of invasive and opportunistic species. It truly is a crabgrass utopia. It is slowly going to seed and going back to nature. A few parts of it, they do maintain but most of that doesn't interest me. Most of it is just a huge, abandoned industrial site. The city uses it for some things, but mostly you can get to a fishing area there, illegal drag racing happens there at night and so on. But really, it is just piles and piles of opportunistic plants configuring these weird shapes that I don't even know how to describe. They're just there. And these plants have no concern for us whatsoever. And that for me is something I'm going to be thinking about for a long time. It's really interesting to me.

Natalie: With that in mind, these plants with no concern for humans, what came to mind when you went one day and saw these giant tents that have been erected in the fields to house migrants?

Benefit Print: New Housing for Asylum Seekers at Floyd Bennett Field, 2024. Screen emulsion on canvas 52 × 68 in | 132.1 × 172.7 cm Edition 1/3 + 1AP.

Proceeds to the benefit of Gowanus Mutual Aid offering support to recently arrived migrants in Brooklyn.

Derek: You know, during COVID I had already been going there a lot. The field and part of it is just empty. There's no one around. I could set up a giant camera and no one's going to mess with me. It's just really beautiful. And also just filled with garbage and trash. It's so beautiful, and it's one of the most annihilated places. Shattered concrete, used condoms…you name it; it is just blown to smithereens. And then I go back, I guess about six months ago, and you can try to hide from history, but history will come and find you. It is no longer an empty place. It is still desolate, but now it's the home to 2,000 people who are recent arrivals in New York City. These are migrants who are hoping to start new lives here. People are seeking political asylum. People are going through our incredibly dysfunctional immigration system. So now there’s five or six hundred families living in Floyd Bennett Field in these giant tents. Each one is maybe half the size of a football field. They are immense tents, five in a row, I think. And they walk across the blasted concrete of the airport about half a mile to a bus stop on Flatbush. And then they have a long ride to get anywhere. There's New York City school buses that pull up in front of the tents and pick kids up. It's actually unbelievable. It's like a town now. Which is shocking.

Natalie: Is this show a small dedication to what Floyd Bennett Field used to be? Are you able to still go and take photographs?

Derek: No, it’s huge. There's no shortage of things that you can still explore. There's an entire four acres of wild prickly pear cactuses, and it’s totally indigenous, not invasive at all. Totally indigenous to the northeast but just very few places they grow. They are thriving. It is just the most beautiful thing. That part looks almost like it was designed by somebody. And the prickly pear cactuses are slowly prying the concrete apart and annihilating it. So no, it's a huge landscape. I have to reckon with the fact that it's people's homes now. People live there now.

Natalie: Hopefully not permanently.

Derek: Yeah I hope not for them. But it's definitely a small 2,000-person community. AndI I hope that with this particular image of the tents - the only image of them in the show - we can raise money for Gowanus Mutual Aid, which is doing a lot of outreach and direct support to recent arrivals in New York. They're a great organization and I hope that image gets some traction.

Kenneth: One more thing in my mind is the role of the modular in your work. There are a lot of works here that are free to be determined by others. I wonder if you could talk a little about the Utopia Library.

Utopia Library, 2018-Present

Derek: So there's about 52 of these small plywood panels with these fancy stickers attached to them, these universal markers. They're small and they can be configured in different ways. They can be deployed in different rooms, by different people in ways that aren’t decided. It's about making an alphabet. It's about this weird idea from the beginning of my career; just the pressure of trying to make a masterpiece. It is usually pretty crippling for artists and it doesn't go that well. So I figured that out kind of early. And instead, I think, what if I tried to make fields of work, where the goal is just citizenship; just trying to make a thing that's good enough to join its fellow citizens in the project. So I don't really have a favorite or too many favorites in that project. They just have to pull a little bit of weight and that power is cumulative. And I find pragmatically, it's an easier way to function in the studio. Suddenly, I'm making without trying to make a masterpiece on any given Tuesday morning. But in aggregate, it starts to really be way more than the singles. It starts to accumulate into something that's really, really great. And I think this installation is terrific and I'm really proud of it. It looks really great here. And I've worked this way throughout my career, this idea of making things that are part of larger fields of work. And how interesting that if you look at the shrubby landscapes in the photographs, there are also similarities to them - they aren’t photographs of the Grand Canyon or something monumental. There's just a low key shrub ethos to them and I think that they just are trying to nestle up against each other as art objects, rather than being these towering masterpieces. It's all very non-monumental in different ways. Like the birds in that image are European Starlings, which are an invasive species. I think they're beautiful and fascinating. But they're an accident. Here they are. And we have to reckon with them. I bet an ornithologist would hate that they're here. But they are. So we have to reckon with it.

Universal Markers, 2018-Present.

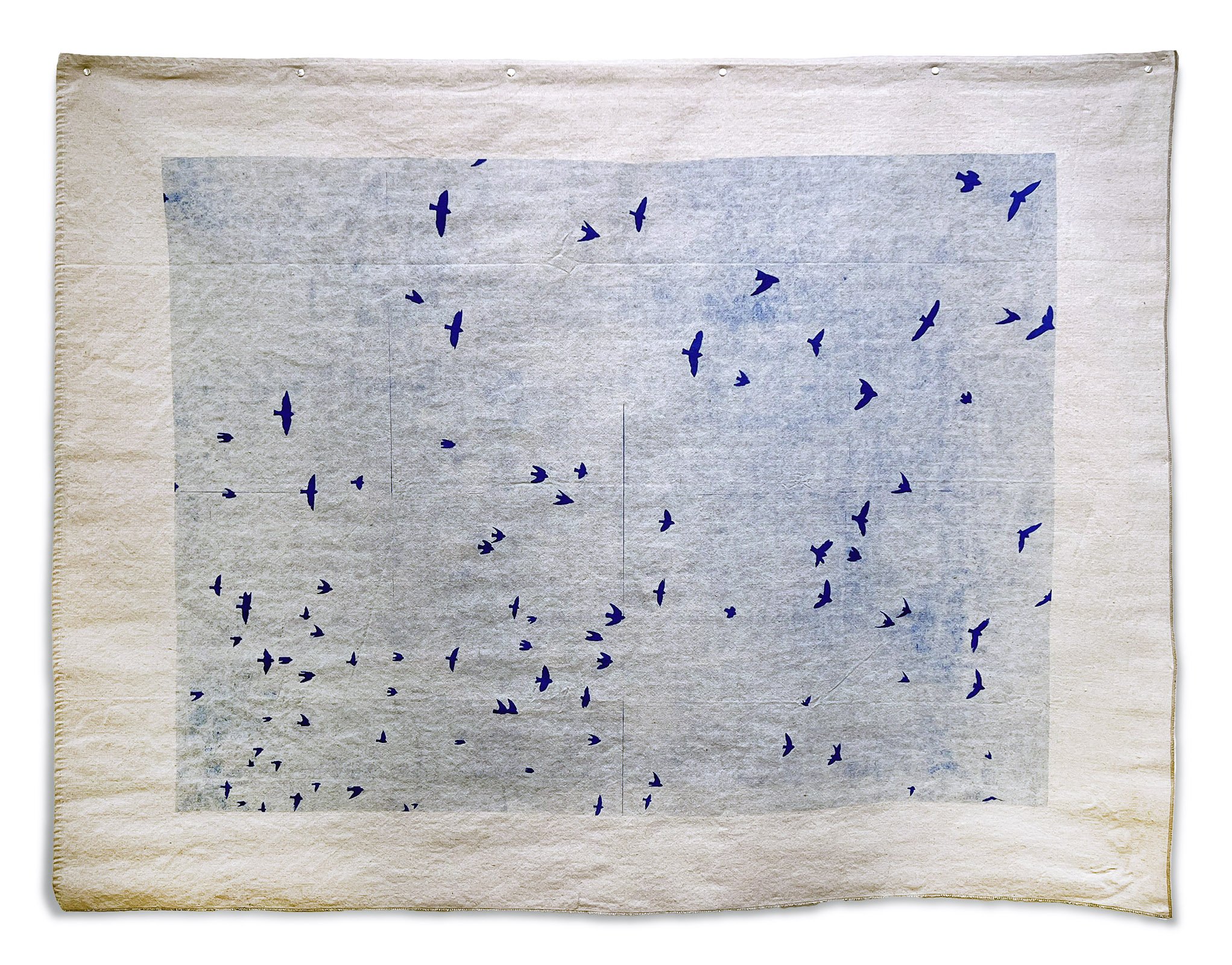

European Starlings (blue), 2023. Screen emulsion on canvas. 52 × 68 inches

Selections from Radiant Fields Series. (All: 2023. Screen print on linen. 29 x 24 inches / 24 x 29 inches. Unique)